The Kentucky Supreme Court heard oral arguments on August 14 from attorneys for the Shively Police Department and The Courier Journal in an open records case that will decide whether law enforcement agencies can deny the public access to all investigative records in an open criminal investigation with or without a showing of harm to the investigation or subsequent prosecution.

https://search.app/U9oMjQpzcFtAtiQ97

A HIGH SPEED POLICE CHASE THAT ENDED IN TRAGEDY PROMPTS AN OPEN RECORDS REQUEST AND A HASTY DENIAL

The open records dispute in Shively Police Department v Courier Journal Inc. originated in Shively's blanket denial of The Courier's request for specific records relating to a July 27, 2020, high speed chase on Dixie Highway which ended when the suspect struck an uninvolved car, "injuring the occupants and ultimately killing three of them."

https://caselaw.findlaw.com/court/ky-court-of-appeals/2001652.html

The suspect was later apprehended and charged with multiple felonies.

Questioning whether Shively officers complied with department vehicle pursuit policies, the Courier-Journal submitted an August 10, 2020, open records request for (1) Computer Aided Dispatch (CAD) reports for services calls; (2) 911 calls; (3) audio communication between dispatch, the responding officers, and any other officers or supervisory personnel; (4) dashcam and bodycam footage; and (5) incident or accident reports.

Shively denied The Courier's open records request, in total, within 36 minutes of receipt. This prompted the newspaper's concern that Shively peremptorily denied

the request without examining the requested records. The department's brief written denial stated:

"As there is an active criminal case regarding this incident, all of the above request are denied under the following exclusion rule: [Kentucky Revised Statutes (KRS)] 61.878 subsection (1)(h)[.]”

Dissatisfied with this response, The Courier bypassed administrative review through the Office of the Kentucky Attorney General and appealed Shively's factually unsupported denial directly to the Jefferson Circuit Court.

The Jefferson Circuit Court found in favor of the Shively Police Department, but the Court of Appeals unanimously reversed.

https://caselaw.findlaw.com/court/ky-court-of-appeals/2001652.html

WHAT THE LAW SAYS AND HOW IT HAS BEEN MISAPPLIED

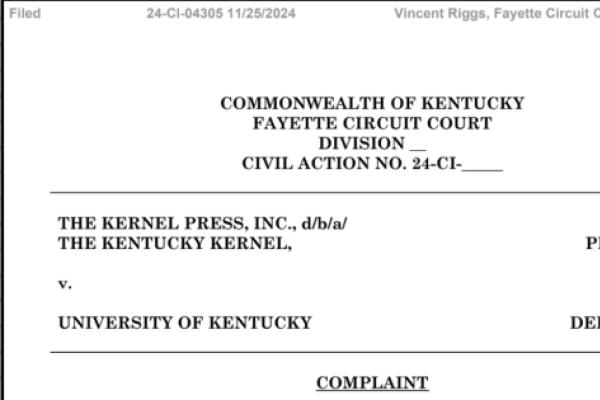

KRS 61.878(1)(h), often referred to as the law enforcement exception, was interpreted by Kentucky's Supreme Court -- in City of Fort Thomas v Cincinnati Enquirer (2013) and University of Kentucky v Kernel Inc. (2021) -- to authorize law enforcement agencies to deny open records requests investigative records in an open investigation only when the agency:

"can articulate a factual basis for applying it, only, that is, when, because of the record's content, its release poses a concrete risk of harm to the agency in the prospective action. A concrete risk, by definition, must be something more than a hypothetical or speculative concern."

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=54126

https://caselaw.findlaw.com/court/ky-supreme-court/1643297.html

https://casetext.com/case/univ-of-ky-v-kernel-press-inc

Shively articulated no risk of harm of any kind -- concrete or speculative -- posed by disclosure of the requested records, asserting only that "there is an active criminal case regarding this incident."

A subsequent affidavit from the chief of the Shively Police Department stated that release would compromise a witness and affect recollection. This "boilerplate" harm is regularly cited in open investigations, is thin on details, and could be vaguely asserted in any open investigation, argued The Courier.

On appeal to the Jefferson Circuit Court, Shively raised more arguments in support of its denial.

In addition to KRS 61.878(1)(h), the department invoked KRS 17.150(2) -- a statute found outside of the open records law -- and KRS 61.878(1)(a), the privacy exception to the open records law.

KRS 17.150(2) is a provision found in the Criminal History Records Act. A criminal records reporting statute mandated by federal law, KRS 17.150(2) is a section of the multipart statute that has been cited by law enforcement agencies and the attorney general over time to justify nondisclosure of all investigative records in an open case, without the required showing that "release poses a concrete risk of harm to the agency in the prospective [criminal] action." Agency reliance on KRS 17.150(2) became particularly common after the Supreme Court made clear in 2013's City of Fort Thomas v Cincinnati Enquirer that a law enforcement agency could not rely on the open records law enforcement exception, KRS 61.878(1)(h), to deny access to investigative records in an open criminal case unless it could demonstrate that release posed a concrete risk of harm to the agency.

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=46877

The attorney general has since endorsed and even expanded this interpretation to include records previously deemed nonexempt like 911 calls and criminal incident reports.

Retired Jefferson Circuit Court Judge John Potter and the Kentucky Open Government Coalition filed an amicus brief in Shively Police Department v Courier Journal Inc., in support of The Courier's position. We examined the legislative history of the open records law and the Criminal History Records Act -- both enacted in 1976 -- to confirm that "KRS 17.150 is an affirmative expression of when records are public, not an expression of when they can be kept secret." In other words, the statute "is a statement of when documents must be produced and is not an implied statement that the records must otherwise remain secret."

The central issue in Shively Police Department v Courier Journal Inc. -- a question directly posed by Justice Michelle Keller -- is whether KRS 17.150(2) effectively swallows KRS 61.878(1)(h), the open records law enforcement exception, it's required showing of a "concrete risk of harm," and its rejection of categorical exemption of records in an open investigation.

THE ARGUMENTS

Representing the Shively Police Department, Shively City Attorney Finn Cato, sweepingly characterized Shively Police Department v Courier Journal Inc. as a case that "focuses on the integrity of criminal justice at large to assist the ability of county and Commonwealth's Attorneys to effectively prosecute criminal cases." He insisted that Shively followed the "directives of limited caselaw and an abundance of attorney general opinions" in discharging its open records duties in this case, and urged the Court to reverse the opinion of the Court of Appeals the effect of which would come "at an enormous financial and administrative cost" to law enforcement agencies.

As noted, Justice Keller posed the central question on appeal when she asked Cato whether KRS 17.150(2) swallows KRS 61.878(1)(h). "No," Cato responded, since it applies only to criminal justice agencies. Cato failed to address the obvious: If a law enforcement agency can indiscriminately rely on 17.150(2) to deny access to all records simply because they relate to an open investigation, doesn't this undermine the limitations imposed by 61.878(1)(h) which require a showing of harm to justify nondisclosure of the records in an open investigation.

When asked to expand on the harm belatedly identified by the Shively's chief in his affidavit, Cato replied that disclosure of the records could, in fact, compromise witnesses and their recollection of events -- harm that is both vague and speculative.

On behalf of The Courier Journal, media law attorney Michael Abate made precisely this point in his argument to the Court.

Abate began his argument by focusing on caselaw establishing the rule for determining if records relating to a pending investigation must be disclosed. That rule, he explained, is "Sometimes but not always."

Abate proceeded with an exhaustive analysis of City of Fort Thomas v Cincinnati Enquirer and University of Kentucky v Kernel Inc. in support of the newspaper's argument that a law enforcement investigatory file is not "categorically exempt" simply because it applies to a prospective enforcement action. Not all records in the file can be withheld because the case is open. Harm is not "presumed."

He underscored the existence of clear judicial guidance on whether and when records in an open investigation must be disclosed. He emphasized that it is not The Courier's position that all investigatory records be must be disclosed, but that the court-established rule mandates some showing of a concrete risk of harm from disclosure.

Shively offered no such proof, Abate asserted, noting that the 36 minute turnaround of the newspaper's open records request would not have been sufficient time to locate the requested records -- much less review them for the risk of harm disclosure might entail.

He asserted that 17.150(2) does, in fact, swallow 61.878(1)(h) and noted that although the Attorney General's erroneous interpretation of 17.150(2) has been a longstanding problem, it has intensified and expanded in recent years as the Attorney General increasingly extended 17.150(2) protection to public records formerly treated as accessible, such as incident reports and 911 calls.

In response to a question fromChief Justice Lawrence Van Meter, Abate acknowledged that City of Fort Thomas v. Cincinnati Enquirer did not address KRS 17.150(2) but urged the Court to affirm the Court of Appeals' analysis. That court harmonized the two statutes when it found that they operate at different times. KRS 61.878(1)(h) applies where a case is pending or prospective. KRS 17.150(2) applies after prosecution is concluded or a decision not to prosecute has been made.

It is the newspaper's position, Abate explained, that KRS 17.150(2) does not protect the records in an open investigation. If it somehow does, he continued, the damage done by the expanding interpretation of that statute can be corrected by "reigning in" its reach.

At a minimum, he urged, KRS 17.150(2) must be "cabined to genuine police work product" -- the officer's mental impressions -- not factual information in video, recordings, and citations, for example. absent a concrete risk of harm.

Abate summarily rejected Shively's belated invocation of the open records law's privacy exception, suggesting that if disturbing images appear in the records, KRS 61.878(4) mandates redaction not wholesale nondisclosure.

He vigorously disputed Shively's claim that the Court of Appeals' and the newspaper's interpretation would place an "an enormous financial and administrative" burden on law enforcement agencies. Abate countered:

"The burden we are talking about is the one this Court set forth in City of Fort Thomas v Cincinnati Enquirer. It is a reasonable and relatively modest one.

"You have to look at the records and you have to give some indication why these records [,if released,] could harm an investigation."

Must the harm be proven? "No," Abate concluded. But it must be more than speculative harm that could be asserted in any criminal investigation.

In closing, Abate urged the Court to affirm the Court of Appeals' unanimous opinion in The Courier Journal's favor.

WHAT'S NEXT

Chief Justice Van Meter concluded oral argument by stating that the Court would issue an opinion as soon as possible.

In the meantime, it is safe to assume that law enforcement agencies will continue to rely on KRS 17.150(2) to deny access to all records in an open criminal investigation. It is also safe to assume that the Kentucky Attorney General will continue to affirm law enforcement's denials of open records requests on this basis.

The decision whether they are legally justified in doing so now rests with the Kentucky Supreme Court.