Senate Bill 63’s foreseeable consequences demand a legislative pause.

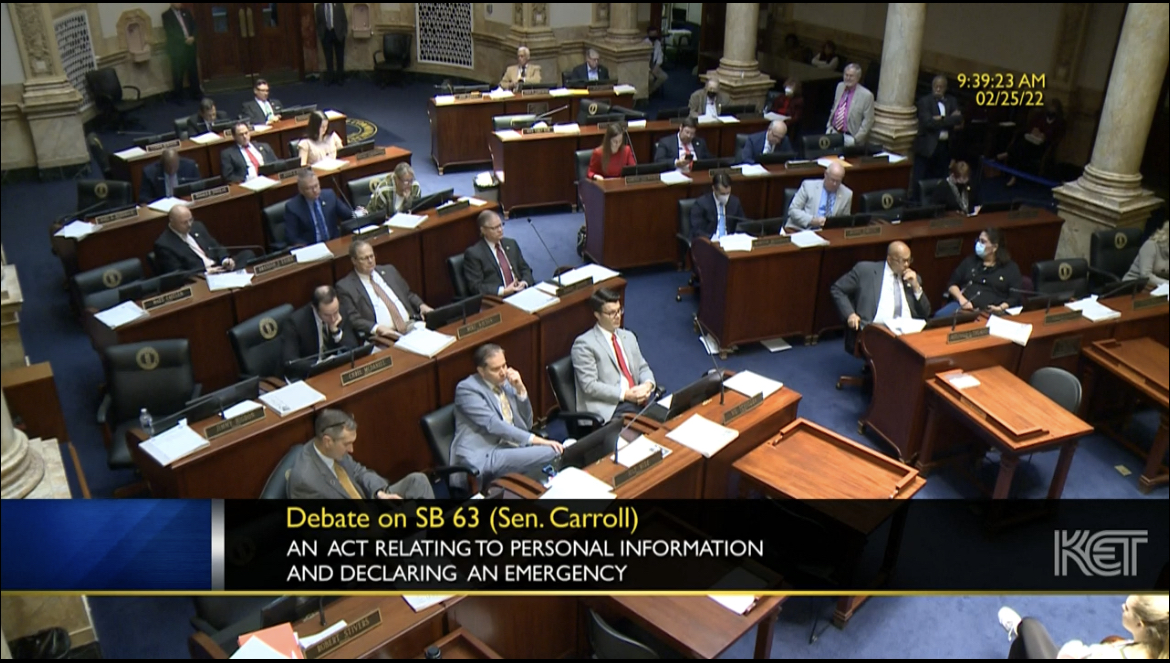

By a vote of 24-8, the Kentucky Senate on February 25 passed a bill that is intended to shield personally identifiable information about certain groups of public officials, and their immediate families, from public access.

That bill, SB 63, sponsored by Senator Danny Carroll, now heads to the House of Representatives.

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/22rs/sb63.html

If the events of the 2021 legislative session are any indicator, SB 63 will also pass in the House of Representatives.

It will be sent to the Governor for signature. At the urging of numerous stakeholders, he is likely to veto SB 63.

To avoid a repeat of 2021 — when they ran out of time — lawmakers will prioritize overriding the Governor’s veto.

Ask lawmakers why SB 63 must pass. They will respond that the personal safety of the public officers to whom the bill’s protection extends depends on overriding the veto.

Ask lawmakers how SB 63 will ensure greater safety for those public officers. They will cite statistics of increased threats to federal judges and attacks on police officers in recent years. They may also cite the 1982 murder of a North Carolina prosecutor by a Kentucky native, the 2000 murder of Kentucky prosecutor Fred Capps, or the 2020 murder of a federal judge’s son in New Jersey.

But they make no claim that the home addresses of the victims in any of these cases was obtained through an open records request. And they offer no explanation for how this bill will erect a barrier to personal information that is widely available on the internet.

Open records laws, they must admit, do not kill people.

At best, they will argue, SB 63 is a first step toward addressing what is, in reality, a symptom of America’s culture of violence. They acknowledge the possibility of “unforeseeable consequences,” offering assurances that they will deal with adverse consequences as consequences present themselves. This is where lawmakers’ narrative breaks down.

Adverse consequences are entirely foreseeable: Daniel’s Law

The New Jersey law on which SB 63 is modeled, Daniel’s Law, was enacted in 2020 and placed on hold in 2021 as New Jersey agencies scrambled to resolve overwhelming challenges of implementation — from anonymously conducting land transfers to confirming the status of those who claim to qualify for protection. The resulting bureaucratic chaos prompted New Jersey lawmakers to fast track remedial legislation in 2022.

https://www.charlesjones.com/news.html?n=9556

While New Jersey officials acknowledged lawmakers’ good intentions, they questioned whether lawmakers seriously considered “how practical it was or how to implement it.”

https://www.law.com/njlawjournal/2021/10/21/confusion-surrounds-impleme…

Those charged with implementation of Daniel’s Law were urged to “use extreme caution when they receive a records request, and consult their lawyer before granting blanket requests.”

https://www.law.com/njlawjournal/2020/10/29/after-tragedies-bills-aim-t…

Under threat of potential liability, public agency response to public records requests ground to a halt. Seeking direction from lawmakers on implementation of the New Jersey law— that was short on detail — public agencies demanded relief.

In the current legislative session, New New Jersey lawmakers are expected to enact remedial legislation aimed at:

• creating a new public agency, the Office of Information Affairs, to process requests for protection of personal information at a substantial cost to taxpayers;

• identifying exceptions for — among other things — documents affecting the title to real property recorded and indexed by a recording office or tax authority; Uniform Commercial Code filings; petitions; liens and other encumbrances; assessment lists; and abandoned property records;

• requiring an acknowledgment that invocation of Daniel’s Law protections may affect “certain rights, duties, and obligations.”

https://www.njlm.org/Blog.aspx?IID=154

If these unintended consequences were not foreseeable before enactment of Daniel’s Law, they are clearly foreseeable now.

Kentucky legislative staff have raised questions about SB 63’s implementation and characterize it’s impact as “indeterminable”

Kentucky’s Legislative Research Commission staff raised similar concerns in a February 22 “local mandate statement,” alerting lawmakers:

“It is unknown how many public officers, or their immediate family members, will request the exemption from disclosure of [personally identifiable information] the impact is indeterminable. With regards to cities, the Kentucky League of Cities estimates that nearly 11,000 city employees within police, fire/EMS, and corrections departments plus around 17,000 volunteer firefighters would qualify as a public officer. KLC also referenced the 8,814 retired members, as of June 2021, in CERS Hazardous and the approximately 1,300 combined retirees and beneficiaries in Lexington’s Policemen’s and Firefighters’ Retirement Fund and City Employees’ Pension Fund. Some cities have their public safety staff in CERS Nonhazardous; therefore, a portion of retirees in that plan may also qualify as a public officer.

“The legislation may prevent localities from publishing certain delinquent taxpayers and/or selling all delinquent tax bills to a third party. With respect to county clerks, the legislation is anticipated to increase duties in already understaffed offices. With the various documents under their purview including those relating to marriages, voter data, vehicle information; there are concerns about the ability to comply. For city clerks, the duties would increase more in smaller municipalities without staff specifically designated to handle only open records requests. In some municipalities, police departments, fire, and emergency management service departments handle their own open records requests and in others, those duties are assigned to city clerk personnel.”

SB 63 directs public agencies to continue to discharge their routine functions, but provides no guidance on how they should do so without risking civil liability.

Ask any Senator, including the bill’s sponsor, how SB 63 will be implemented?

We asked. The press association and broadcasters association asked. Senators opposing the bill asked.

The bill’s advocates responded with statistics, references to random tragic incidents with no correlation to public records laws, and assurances that unforeseen consequences — adverse consequences that are actually foreseeable and foreseen — to public agencies, and to the public statutory right to know, will be addressed in future legislative sessions.

Does the sponsor of the bill, or the 23 senators who voted for it, have any idea how a public agency —“responsible for” records containing “personally identifiable information“ — will continue to discharge the “routine functions” that necessitate the maintenance and use of those records if/when a “public officer or immediate family member“ protected under SB 63 notifies the agency that s/he “does not want the information to be made public.”

How will the agency utilize the records to perform its routine functions while preserving the confidentiality of the designated personally identifiable information and ensuring that it is “not posted, re-posted, published, or otherwise made known” at the risk of potential civil liability?

Foreseeable adverse consequences are also confirmed by Kentucky public officials charged with enforcement

Not long after SB 63 gained traction in the current session, The Owensboro Messenger Inquirer asked local officials how the bill might impact their “routine functions.”

The Messenger Inquirer quoted two property valuation administrators who expressed concern about their ability, as well as the ability of county clerks, to conduct “a lot of regular business.” As in New Jersey, one of those officials — William “Mack” Bushart, executive director of the Kentucky Property Valuation Administrators Association — noted that much of the “protected” information is, in all likelihood, already available elsewhere.

https://www.messenger-inquirer.com/news/bill-would-exempt-public-offici…

More from public officials charged with implementation is likely to follow.

Proponents and opponents agree that protection of “public officers” is a worthy goal. They fundamentally disagree on whether SB 63 is a practical means to that end.

But let’s leave “unforeseeable consequences” out of the equation.

The New Jersey experiment, Kentucky’s legislative staff, and local officials charged with implementation confirm the adverse foreseeable consequences.

At the heart of the SB 63 debate rests the four and one-half decades old open records law. The chilling effect on public agency discharge of “routine functions” — which include fulfillment of open records request — under threat of civil liability will result in the first and most serious adverse consequence.

Only one thing is actually unforeseeable: Whether the Kentucky General Assembly is sufficiently committed to public officers’ safety, public officials’ ability to discharge their public duties, and the public’s right to know to hit the pause button on SB 63, an arguably well-intentioned but ill-conceived proposal that will yield little, if any, net benefit.