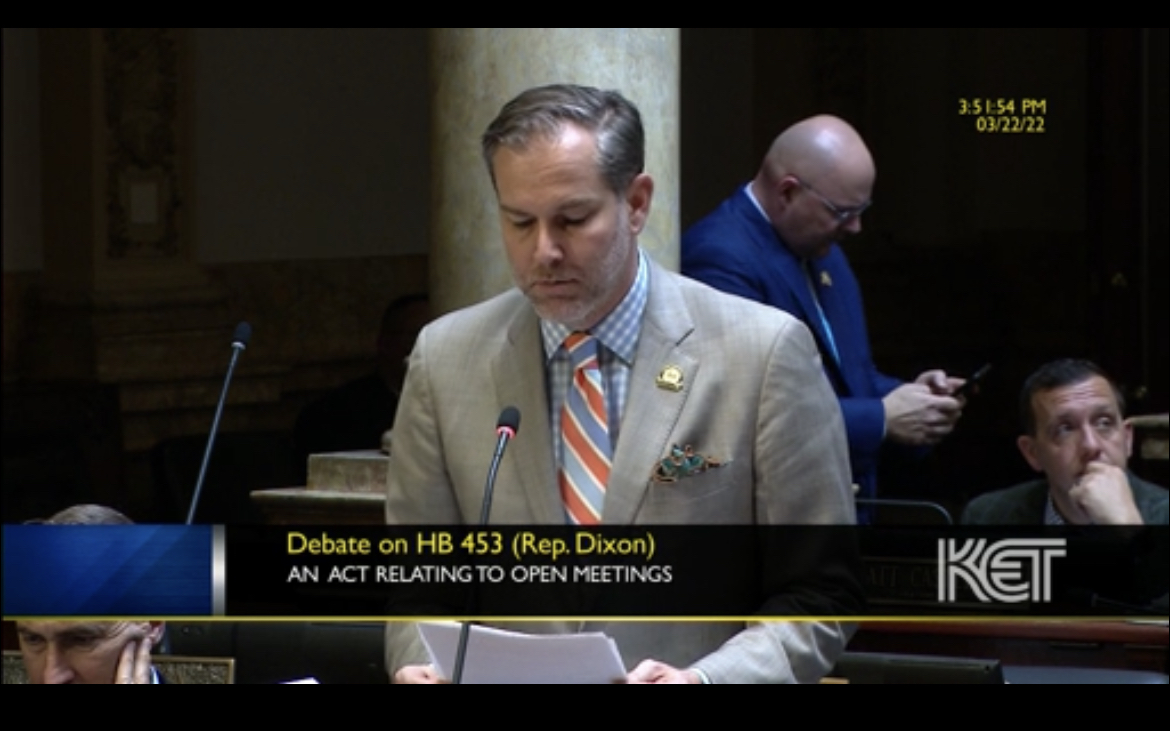

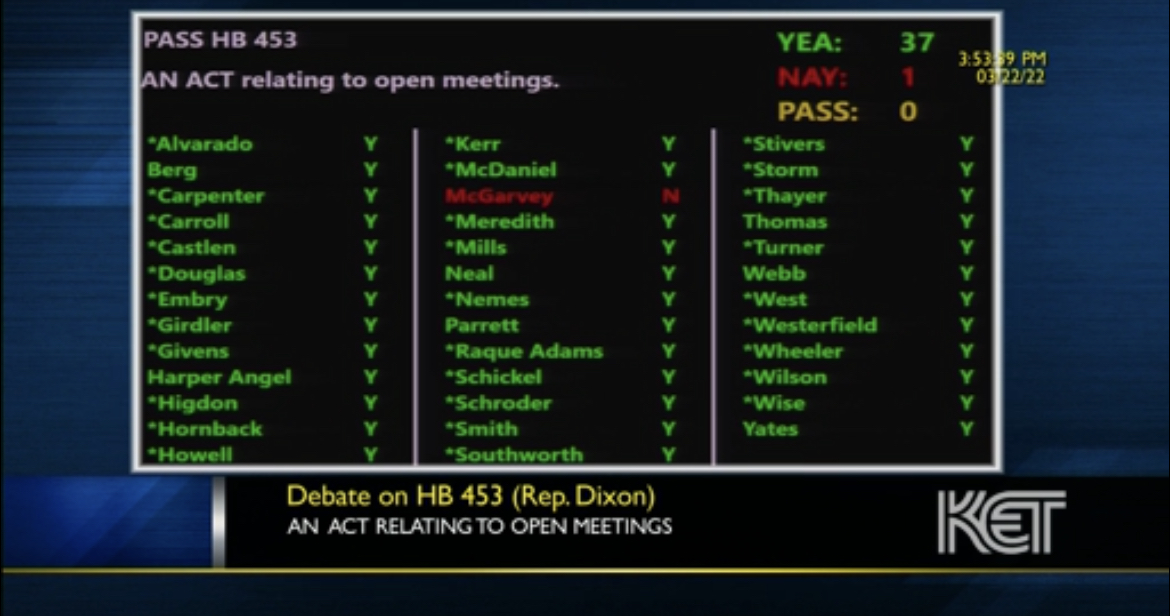

With no discussion — and only one dissenting vote — HB 453, “An Act relating to open meetings,” sailed through the Senate on March 22 despite the Kentucky Open Government Coalition’s best efforts to alert lawmakers to the threat to the Open Meetings Act the bill poses.

On March 23, the Coalition submitted the following Request for Veto of HB 453 to Governor Andy Beshear.

To summarize, the Coalition’s objections are based on our concern that:

• video teleconferenced meetings, as we have come to understand them under the temporary modifications to the Open Meetings Act necessitated by public health concerns, were not intended to become a permanent legal substitute for in person meetings or create a legal mechanism by which public officials might insulate themselves from the constituents they serve;

• codification of KRS 61.826 as a permanent video teleconferencing law, as we have come to understand that term in the past two years, will discourage in person meetings for which the Kentucky Open Meetings Act has always demonstrated a strong preference;

• KRS 61.826 lacks sufficient safeguards to protect the public’s ability to observe public meetings and lends itself to abuse; and

• the General Assembly has given no consideration to the “hybrid” open meetings model that has been adopted or is under review in other states and that requires both in person and live streamed meetings aimed at promoting the broadest possible public participation.

Given the enormity of the task that lies ahead for the Governor, we are not optimistic that we will achieve our goal, or that — if achieved — lawmakers won’t quickly move to override his veto.

This, sadly, is the world we live. But those who remain committed to “the health of our democracy” will not surrender in the face of overwhelming odds.

The Kentucky Open Government Coalition’s Request for Veto of HB 453 follows:

March 23, 2022

Kentucky Open Government Coalition

612 S. Main St./Suite 203

Hopkinsville, KY 42240

Honorable Andy Beshear

Governor, Commonwealth of Kentucky

The Capitol

Frankfort, Kentucky 40601

Re: Request for Veto of House Bill 453

Dear Governor Beshear:

The Kentucky Open Government Coalition respectfully requests that you veto HB 453.

The Coalition is a nonpartisan Kentucky nonprofit corporation founded in 2019. We are one of 39 citizen-driven state, territory, and district members of the National Freedom of Information Coalition.

From our inception, the Coalition has identified transparency and accountability as core principles. Our purpose is to enhance public understanding of, and preserve existing public rights under, the Kentucky open records and meetings laws. We serve as a citizens’ voice for open government.

It is our position that House Bill 453 threatens the preference for in person meetings that has existed in the Open Meetings Act since its enactment. It abridges the public’s right to make its collective “voice“ heard in face to face interaction with its elected and appointed officials by authorizing those officials, without limitation, to erect electronic barriers to the public's ability to hold them accountable at in person.

The Coalition believes that the better course for Kentucky is the hybrid option for public meetings. A hybrid meeting is one that is conducted in person and simultaneously live streamed. Hybrid meetings promote the broadest possible public participation, but the hybrid option has not been considered by the General Assembly.

Nor has the General Assembly demonstrated any interest in imposing necessary safeguards on “video teleconferenced/virtual” meetings.

•The backstory of HB 453

The Coalition understands the need for legislative action to extend the modifications to the Open Meetings Act. Those modifications were temporarily adopted in 2020’s SB 150 and extended through April 2022 under 2022’s SB 25. Public agencies across the state have developed and improved technologies for conducting “virtual” meetings in the last two years. While still imperfect, “virtual” meetings have promoted public participation and ultimately redounded to the public’s benefit, and especially to the public’s health, during the COVID crisis.

What has been lost in this debate, however, is the reality that these temporary modifications were necessitated by public health concerns. They were not intended to become a permanent legal substitute for in person meetings or create a legal mechanism by which public officials might indiscriminately insulate themselves from the constituents they serve.

•Arguments in support of your veto of HB 453

In addition to creating two new, unvetted exceptions to the Kentucky Open Meetings Act, House Bill 453, as noted, permanently codifies the right of public agencies to conduct public meetings by “video teleconference,” as that term has been used since public health issues associated with the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated a departure from traditional in-person meetings in favor of a safer alternative: “virtual meetings.”

While the Kentucky Open Government Coalition opposes the introduction of new exceptions to the Open Meetings Act where there is no demonstrated need for those exceptions, we recognize that HB 453 is otherwise facially innocuous. Looks, in this case, are deceiving.

•”Video teleconferencing” is not synonymous with “remote participation” or “virtual meetings”

What are loosely described as a “video teleconferenced” meetings in HB 453 are actually “virtual” meetings. They were not intended as a permanent — and in many respects inferior — substitute for in person meetings.

“Video teleconferenced” meetings have existed in the Open Meetings Act at KRS 61.826 since 1994. The term was loosely defined in that pre-Internet era, to describe “one meeting, occurring in two or more locations, where individuals can see and hear each other by means of video and audio equipment.” KRS 61.805(5).

The goal of the 1994 law was to expand opportunities for Kentuckians residing hundreds of miles from a public agency’s in-person meeting site to “attend” at designated meetings sites that afforded them the ability to see and hear the meeting by means of a video teleconference.

The example often given was a University of Kentucky Board of Trustees’ meeting, conducted in Lexington, at which tuition hikes were to be discussed. Parents of UK students from across the Commonwealth had an interest in the topic but not always the means to attend the meeting in person. If the Board provided video teleconferencing opportunities, and located and identified meeting sites that supported video teleconferencing, parents could “attend” the meeting to observe the discussion of tuition increases — that would directly affect them — without traveling to Lexington.

In this example, the Board conducted an in person meeting in Lexington to which the public was physically admitted. If it elected to provide video teleconferencing of its in person meeting under KRS 61.826, the Board was required to provide meeting notice that identified the video teleconferenced meeting sites and which, if any, was the primary location. It was required to suspend the in person meeting if there was any disruption in the audio or video broadcast. Finally, it could not conduct a videoteleconference of any meeting at which a closed session was planned.

This little used statute — aimed at promoting broader public participation — was modified in 2018 to permit “remote” participation of a non-present member at an in person meeting of the public agency. The General Assembly deleted the only legal impediment to the use of KRS 61.826 for this purpose — which prohibited closed sessions at video teleconferenced meetings — to accommodate public officials’ convenience.

In our example, a non-present UK Board trustee traveling abroad could participate in an in person meeting, including a closed session, from a hotel room in Europe.

Other states’ open meetings laws permit this practice but established safeguards on its use, including required roll call votes, a minimum number of in person meetings, and limits on the number of a member’s unexcused absences from in person meetings. Even as amended in 2018, KRS 61.826 did not suspend the requirement of in person meetings or create a pre-pandemic option to conduct “virtual meetings” to which the public was “admitted” through an electronic link.

•The Open Meetings Act's preference for in person meetings

The Kentucky Open Meetings Act exhibits a preference in favor of in person meetings.

Although the courts have had few occasions to address the issue, in 1977 the Supreme Court declared void the Jefferson County Fiscal Court’s telephonic meeting and vote on the public business with which the fiscal court was charged. Jefferson County Fiscal Court v. Courier Journal and Louisville Times, 554 SW2d 72 (Ky. 1977).

The Court’s ruling disfavored electronic participation in lieu of physical presence.

The law itself envisions “meeting room conditions, including adequate space, seating, and acoustics, which insofar as is feasible allow effective public observation of the public meetings.” KRS 61.840.

In Jefferson County Fiscal Court v. Courier Journal and Louisville Times, above, the Kentucky Supreme Court recognized a foundational principle that adheres in the law, eloquently attested to by the editorial board of the Virginia Daily Progress in the early days of the pandemic:

“While avoiding personal contact is important to our physical health at this time, it is not ideal for the health of our democracy over the long run.

“Our leaders must commit to a return to open meetings at shared locations just as soon as the all-clear is given. Electronic meetings might protect them from the discomfort of confronting their critics in person.

“But democracy cannot thrive in such an environment.”

https://www.dailyprogress.com/opinion/opinion-editorial-democracys-heal…

•The hybrid model for public meetings promotes maximum public participation

Great efforts have been expended in other states to preserve accountability through in person meetings and to simultaneously expand public participation through “virtual” meetings. Hybrid meetings — which combine requirements for in person and virtual public meeting employing technology mastered during the pandemic — best serve the public’s interest.

Despite the Kentucky Open Government Coalition entreaties, the General Assembly did not consider the hybrid meeting option, instead electing to sacrifice “the health of our democracy” by giving public agencies the unfettered discretion to conduct virtual public meetings, and abandon in person meetings, thus evading the discomfort of public opposition on contentious issues.

Nor did the General Assembly establish adequate safeguards for conducting “virtual” meetings, described as video teleconferenced meetings, under HB 453. These guardrails include:

• mandatory roll call votes with microphones on;

• electronic distribution of meeting materials to be discussed at the same time the materials are distributed to agency members;

• a dedicated phone line for citizens to report disruption of the audio or video signal as the meeting proceeds;

• steps to ensure any visual aids presented to agency members are equally visible to the public;

• measures aimed at ensuring that public agency members are not secretly communicating by email or text by members or nonmembers during the public meeting or secretly admitting nonmembers into closed sessions at their “virtual” meeting sites; and

• a fixed minimum number of in person meetings each year.

The Coalition supports inclusion of the new language in HB 453, requiring agency members who participate in a virtual meeting to “remain visible on camera at all times that business is being discussed.”

This requirement provides at least some protection for the public’s right to fully participate in a public meeting, but affords minimal reassurance. For these reasons, the Kentucky Open Government Coalition respectfully requests that you veto HB 453. Nothing less than “the health of our democracy” rests in the balance.

We welcome the opportunity to discuss our concerns with you.

Respectfully submitted,

The Kentucky Open Government Coalition Board Members

Amye Bensenhaver, Frankfort

Jennifer P. Brown, Hopkinsville

Scott Horn, Lexington

Tom Kiffmeyer, Morehead

Jeremy Rogers, Louisville