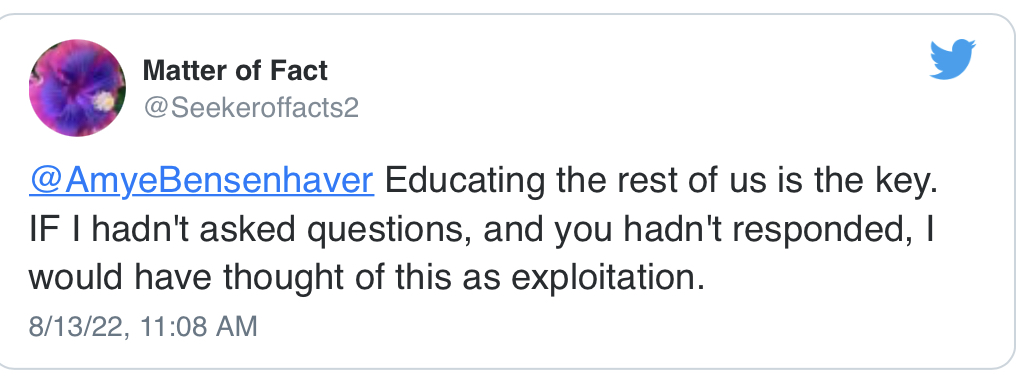

A Kentucky Open Government Coalition post about a report from The Tennessean that the family of country singer Naomi Judd recently filed an amended petition in a Tennessee court to seal reports and recordings made during the investigation into her death prompted an important Twitter discussion.

https://twitter.com/seekeroffacts2/status/1558470587122581506?s=11&t=hf…

The Tennessean noted that petitioners stated the release of the investigative records would cause "significant trauma and irreparable harm" to family members.

The Tweeter expressed doubt about the public’s need to know the “last minute details” of the singer’s tragic death. “She passed, she can't be brought back, and this would hurt those that are closest to her. Unless foul play is suspected, why would anyone need to know.”

Her tweet reflects a valid concern for personal privacy. Objections to public records disclosure of police investigative records and death scene/autopsy photos gained momentum following the death of NASCAR driver Dale Earnhardt and a legal battle waged by Earnhardt’s widow to seal autopsy photo. Its current manifestations include investigative records and death scene photos of comedian Bob Sagat and NBA superstar Kobe Bryant.

https://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/fl-xpm-2004-04-13-0404120459-story.ht…

https://floridapolitics.com/archives/500053-bob-saget-autopsy-photos-ca…

https://www.cnn.com/2022/08/13/us/kobe-bryant-crash-photos-lawsuit/inde…

Doubtful that I would make much headway, I explained:

“The open records law focuses on a public agency employee’s discharge of public duties. Public records—for example, dispatch records and 911 calls on or before the date of Naomi Judd’s death—would confirm (or not) that public employees properly discharged their public duties.”

I pointed out:

“The same records might reveal weaknesses in the dispatch/911 system that require correction. Consider what Kentucky learned from [disclosure of ] child fatality records maintained by [the Cabinet for Health and Family Services]. To the extent the decedents’ [HIPAA rights—which survive death] or their families’ privacy requires protection, the privacy exception is available.”

Never at a loss for words to defend the open records law, I quoted the case:

“Child fatality files are subject to the open records law ‘to ensure both the cabinet and the public do everything possible to prevent the repeat of such tragedies in the future. There can be no effective prevention when there is no public examination of the underlying facts.’”

I directed the Tweeter’s attention to this 2016 Courier Journal article:

“Kentucky cabinet penalized $756,000 for ‘willfully circumventing’ child-abuse open records ruling, judge says”

https://t.co/6vCPxS0dC8

I also emphasized the following statement from a 1992 Kentucky Supreme Court opinion, Kentucky Board of Examiners of Psychologists v Courier Journal:

“The public's right to know under the Act is premised upon the public's right to expect its agencies properly to execute their statutory functions. The policy of disclosure is purposed to subserve the public interest, not to satisfy the public's curiosity.”

https://law.justia.com/cases/kentucky/supreme-court/1992/90-sc-498-dg-1…

I was very pleased by the Tweeter’s open-mindedness. She responded:

“So this isn't so much about exposing her and the family as it is about the system.”

A productive exchange that ended well.

This is what the Coalition does and why we do it. We explain the value and importance of Kentucky’s open government laws and try to correct misunderstandings—or in the case of state legislators who are hostile to the law—misrepresentations about the law.

In some cases—like Sunday’s Twitter exchange—we succeed in convincing doubters that disclosure of public records is rarely, if ever, gratuitous.

Sadly, we were unsuccessful in our 2021 efforts to convince Kentucky lawmakers that a proposed open records exception for “photographs or videos that depict the death, killing, rape, or sexual assault of a person” was duplicative and potentially harmful. Our argument that the privacy exception—which has existed in the open records law since its enactment—provides adequate protection for such records if their disclosure does nothing to advance the public’s right to know whether public officials and employees are properly discharging a public duty fell on deaf ears. That exception is now codified at KRS 61.878(1)(q), and would arguably authorize public agency nondisclosure of, for example, the bystander video in the George Floyd case or the surveillance video in the David McAtee case.

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=51393

https://www.kyopengov.org/blog/without-discussion-bill-creating-new-exc…

In 1976, the legislative architects of Kentucky’s open records law envisioned circumstances in which the competing public and private interests in inspecting public records might be equally, or nearly equally, weighted by including the “clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy” language in the privacy exception.

In 1992 Kentucky’s courts established a balancing test for application of the privacy exception to ensure that disclosure advances the public’s right to know rather than simply satisfying the public’s curiosity.

If only the minds of Kentucky’s lawmakers were as open as @Seekeroffacts2