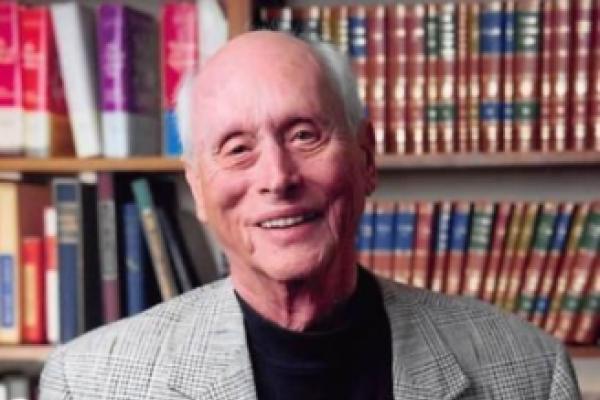

Judge Phillip Shepherd’s victory secures the future of open government in Franklin Circuit Court for the next eight years.

The Kentucky Open Government Coalition watched the nonpartisan judicial race with great interest, knowing that a substantial number of open records cases begin in the Franklin Circuit Court and that Shepherd’s track record on open government disputes is a strong one.

This is not to say that we have always agreed with Shepherd. But he has been a steady voice of reason in a fractious area of law that, at its most basic level, enables the public to hold its public servants accountable.

It was Shepherd who, in litigation concluded at the trial court level in 2014, exposed a “culture of secrecy” within the Cabinet for Health and Family Services that rendered it “institutionally incapable of recognizing and implementing the clear requirement of the law," obscuring failures in child protective services documented in jealously guarded child fatality and near fatality records.

It was Shepherd who rejected the Bevin administration’s attempt to illegally conceal the actuarial analysis of the former governor’s later discredited 2017 pension reform plan. “The stakes are so high,” Shepherd ruled “the need for full public disclosure of all relevant information to inform public debate is equally high.”

And it was Shepherd who, in a recent open records trifecta:

• rejected the Kentucky Public Pension Authority’s denial of Louisville attorneys Jordan White’s and Glenn Cohen’s open records requests for the Calcaterra Pollack investigative report into improper and illegal investment activities by the Kentucky Retirement Systems, declaring “the public paid $1.2 million dollars for the report. The public has a right to know its contents and decide if it got what it paid for”;

• rejected the Kentucky Attorney General misplaced reliance on the preliminary documents and law enforcement exceptions to the open records law, ruling that Daniel Cameron violated the open records law in denying American Oversight access to records related to his election integrity task force. Shepherd rejected Cameron’s effort to shift the burden to the public, declaring that a requester “cannot be expected to know all relevant search terms or places where the agency may file such records. To place that burden on the requestor is to invite the agency to hide relevant records that are obscurely labeled or stored in deep recesses of its bureaucratic records system. It is the duty of the agency to conduct and open, thorough, and good faith search of its records in response to an Open Records request”; and

• rejected Kentucky State University Foundation’s argument that it is not a public agency and therefore not subject to the open records law. “As an arm of Kentucky State University [that exists solely] for the purpose of fundraising and support of KSU’s students, faculty, programs and mission,” he found, the foundation is accountable to the public through its records. “If the principal (KSU) is subject to the Open Records Act, then the agent (KSU Foundation) must also be subject to the Open Records Act.”

Were it otherwise, “the plain requirements of the Open Records Act would be ridiculously easy to circumvent, the stewardship of funds held in trust for a public university would be shielded from public scrutiny, and the purpose of the Open Records Act would be completely thwarted.”

Simply put, Shepherd has a firm grasp of the open records law, the policies that support it, and the inclination of some public agencies to expend enormous energy (and taxpayer dollars) to circumvent it.

His victory is, in no small part, a victory for open government.