A few open government quick takes from the 2022 legislative session.

Public comment

Representative Regina Huff’s HB 121 — requiring a 15 minute public comment period for school board meetings — received mixed reviews but became law without the Governor’s signature.

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/22rs/hb121.html

The open meetings law does not require public agencies to provide opportunities for public comment.

Past Kentucky Attorneys General urged public comment at all public meetings in open meetings decisions, and the practice is widely employed.

HB 121 does not amend the open meetings law.

Narrowly limited to school board meetings, many believed the bill targeted the Jefferson County Board of Education. JCPS briefly suspended public comment at the height of the controversy about school resource officers.

Certainly, superintendents and school districts across the state have expressed concern about this usurpation of local authority that will necessitate changes in existing public comment policies.

https://www.somerset-kentucky.com/news/local-school-leaders-react-to-ho…

Anti-SLAPP

Wisely, Kentucky lawmakers at long last enacted an anti-SLAPP law aimed at swift dismissal of frivolous lawsuits filed for no other purpose than to chill citizen exercise of First Amendment rights.

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/22rs/hb222.html

SLAPP is the acronym for Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation. The concept was foreign to us when we first learned how SLAPPs have been used to discourage open government advocates. We watched a SLAPP unfold in Taylorsville, Kentucky when the city sued a frequent open records requester and open meetings complainant for compensatory and punitive damages related to his access to and publication of public records.

The Spencer Circuit Court — and later the Kentucky Court of Appeals — excoriated the city in a published opinion. https://cases.justia.com/kentucky/court-of-appeals/2020-2019-ca-000152-…1592575365

In affirming the circuit court’s dismissal of the city’s SLAPP, the Court of Appeals declared, “ORA does not provide a remedy to the City or to any government entity to seek civil damages for the publication of a document, even one exempt under the ORA. To put the matter a different way, the government can use the ORA as a shield; it cannot use it as a sword.”

But City of Taylorsville Board of Ethics v Trageser languished in the courts for three years. An anti-SLAPP law would likely have brought the case to a swift conclusion, sparing the courts, the taxpayers, and Trageser needless time and expense.

For more on Kentucky SLAPPs, see https://kyopengov.org/blog/kentucky-supreme-court-opinion-presages-pass…

Records creation and management

Kentucky’s open records and records management laws are statutorily deemed “essentially related” at KRS 61.8715. Sound public records management, the law recognizes, facilitates ease of records access.

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=50009

A premier public records and records management program within the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives evolved over several decades. Following the enactment of KRS 61.8715 in 1994, KDLA and the Kentucky Attorney General established a collaborative open records appeal referral process to enable KDLA to improve public agency records management practices in appeals involving agencies where records mismanagement resulted in records access disputes.

By law, KDLA’s Public Records division and the Libraries, Archives, and Records Commission is charged with establishing records retention schedules and records destruction certification processes. They have successfully done so for many years.

True to form, lawmakers usurped KDLA’s role in 2022, enacting legislation that creates a separate and arguably conflicting mechanism for notification of records destruction by allowing local governments to submit an affidavit of loss, damage, or destruction of a public records in lieu of the records to the Legislative Research Commission or the “state.”

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/22rs/HB351.html

Additionally, lawmakers established retention periods for records generated, for example, in student disciplinary proceedings conducted by post-secondary educational institutions under the newly enacted HB 290. Universities are directed to retain administrative files permanently if a violation results in the expulsion of a student. If not, lawmakers direct universities to retain the files for three years after the respondent's graduation, last date of attendance, or after all sanctions have been met.

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/22rs/HB290.html

These are additional instances of legislative centralization of formerly executive branch authority.

New open meetings exceptions

There was a time when the introduction of sweeping new exceptions to the open records and meetings laws was unusual and, generally, unwelcomed. New “exceptions” were carefully carved out and embedded in agency specific statutes that were incorporated by reference into the open records and meetings laws.

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=51393

For the first twenty years of the laws’ existence, lawmakers enacted only one new open records exception — one other exception was rewritten and broken out into component parts for the sake of clarity — and no new open meetings exceptions. The first major open records and corresponding open meetings exceptions were enacted eleven years later in 2005 — a carefully vetted homeland security exception enacted four years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. A far less consequential exception relating to archival materials accepted from “a donor or depositor other than a public agency” — for example, the University of Louisville’s acceptance of Mitch McConnell’s papers — was enacted in the same year.

In other words, new exceptions were few and far between.

This is manifestly not so in the current legislative environment.

Indeed, it has become so common for lawmakers to add new exceptions that we barely take notice. SB 63 — Senator Danny Carroll’s ill-conceived and poorly drafted bill amending the open records law — died in the 2022 session but contained a sweeping exception for “public records containing personally identifiable information of a public officer or his or her immediate family member if that officer has notified the public agency responsible for those records that he or she does not want the information to be made public.”

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/recorddocuments/bill/22RS/sb63/bill.pdf

The list of exceptions to the open records law has expanded from 14 to 18 in the period from 2018 to 2022. But for the opposition of the press and the public, there would be even more.

The 2022 legislative session witnessed the enactment of two new open meetings exceptions aimed at facilitating greater secrecy in local government procurement and performance evaluations of city managers. If and how these exceptions will be used, and perhaps abused, remains to be seen.

Shadows of 2021 legislation

With the exception of the newly enacted anti-SLAPP law, it is likely these new laws will adversely impact existing rights of public access.

Certainly, those laws enacted in 2021 have had adverse lingering effects.

Consider, for example, the new residency requirement for users of the Kentucky open records laws that prevented a University of California Santa Barbara student researcher from accessing Kentucky data for nationwide analysis. Or consider the impediments encountered by Colorado residents in accessing investigative records into their son’s death in the custody of the Richmond Police Department. Finally, consider the imaginative misapplication of the residency requirement to require Kentucky requesters to produce proof of residency or conduct onsite inspection of public records.

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/21rs/hb312.html

Who could not foresee the problems with a new exception to the open records law for “photographs or videos that depict the death, killing, rape, or sexual assault of a person?” The Kentucky Open Government Coalition identified several — focusing on surveillance and bystander videos of the murders/deaths of George Floyd, David McAtee, Ahmaud Arbery, and even Jeffrey Epstein — but our arguments fell on deaf ears. The Coalition could not have imagined, one year later, the increasing number of jail surveillance videos of inmate deaths that are publicly inaccessible thanks to the ostensibly harmless new exception.

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/21rs/hb273.html

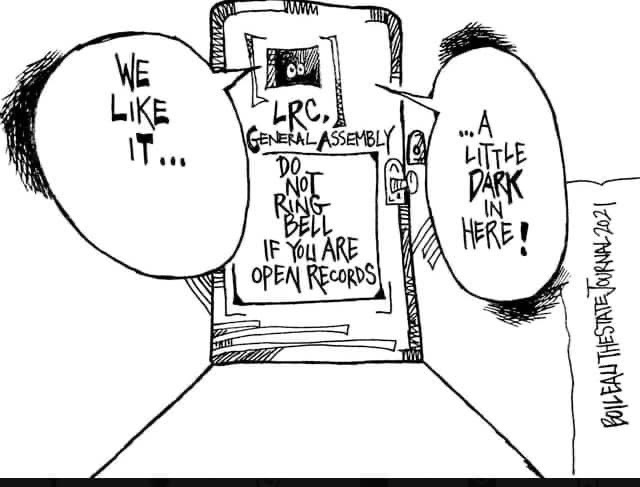

And finally, who could have imagined a more cynical and self-serving 2021 enactment than the law exempting the Legislative Research Commission and the General Assembly from the open records law, establishing a separate mechanism for accessing the absurdly narrow subset of records lawmakers deem “public,” and precluding judicial review of denial of legislative records requests.

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/21rs/hb312.html

Without exception, these provisions — and others enacted in 2021 — have had devastating consequences for the public’s right to know.

Expect 2022’s new laws — excluding the newly enacted anti-SLAPP law — to have the same adverse consequences.