It didn’t take long for the Kentucky Public Pension Authority to respond to the followup open records request and open meetings complaint filed last week in the wake of the long overdue release of the $1.2 million taxpayer funded Calcaterra Pollack report.

In both cases, KPPA issued quick denials.

And in both denials, KPPA signaled there would be no change in the “culture of secrecy” that pervades the agency.

“Culture of secrecy.” That now hackneyed phrase has lost its sting since Franklin Circuit Court Judge Phillip Shepherd used lit to describe the Cabinet for Health and Family Services’ refusal to disclose records revealing systemic agency failures that contributed to the deaths of children under its supervision in 2013.

https://caselaw.findlaw.com/ky-court-of-appeals/1726554.html

The record in the CHFS case confirmed that abuses would continue to occur, Judge Shepherd wrote, "as long as the they remain[ ] effectively shielded from public scrutiny."

The same is true of abuses at KPPA.

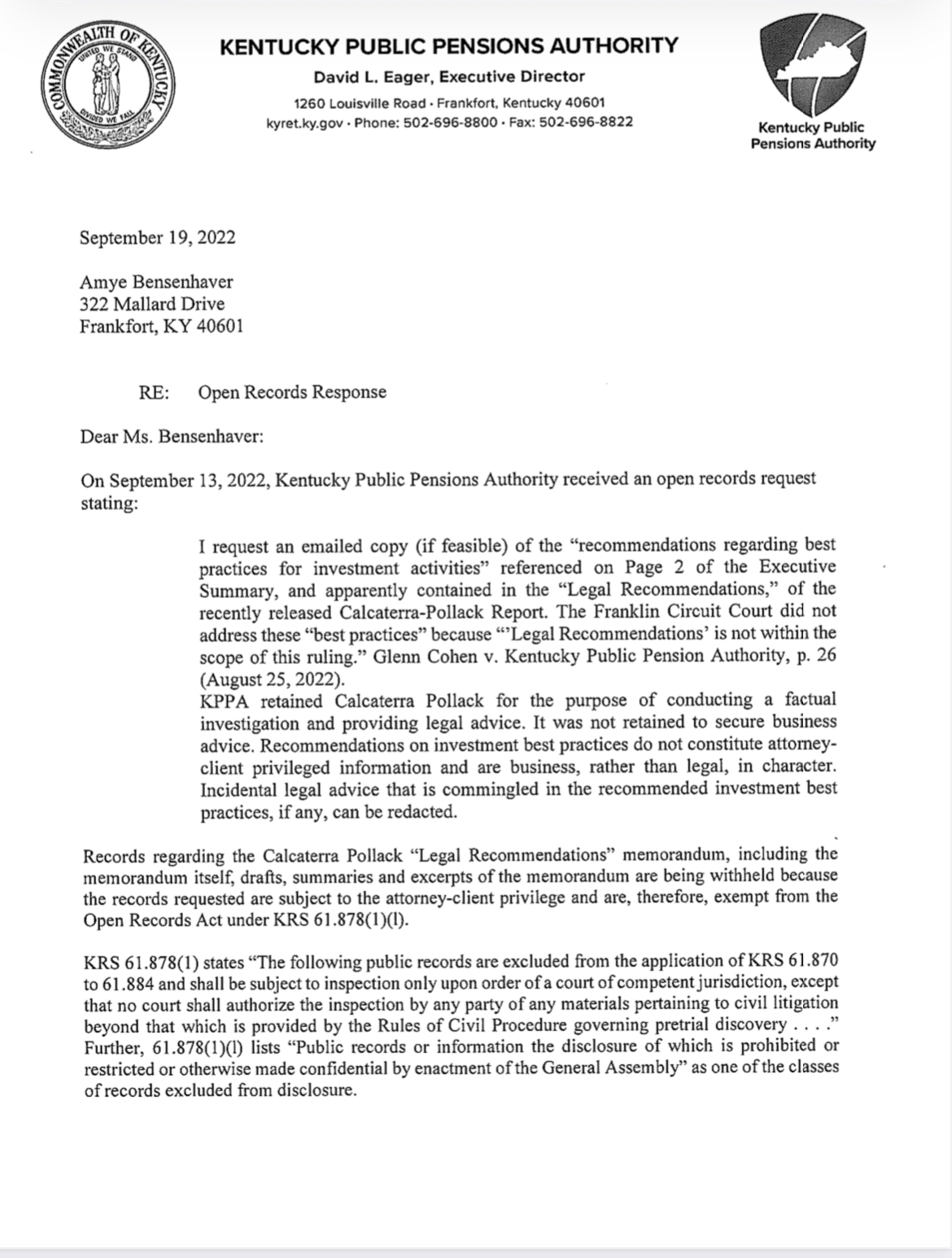

On September 13, we submitted an open records request to KPPA for the “‘recommendations regarding best practices for investment activities’ referenced on Page 2 of the Executive

Summary, and apparently contained in the ‘Legal Recommendations,’ of the recently released Calcaterra-Pollack Report.” We asserted that KPPA contracted with Calcaterra to provide “legal advice . . . [and not] to secure business

advice.”

“Recommendations on investment best practices,” we maintained, “do not constitute attorney-

client privileged information and are business, rather than legal, in character.” We emphasized

“the substantial public interest in knowing Calcaterra Pollack’s recommended investment best practices and monitoring the extent to which KPPA has implemented them.”

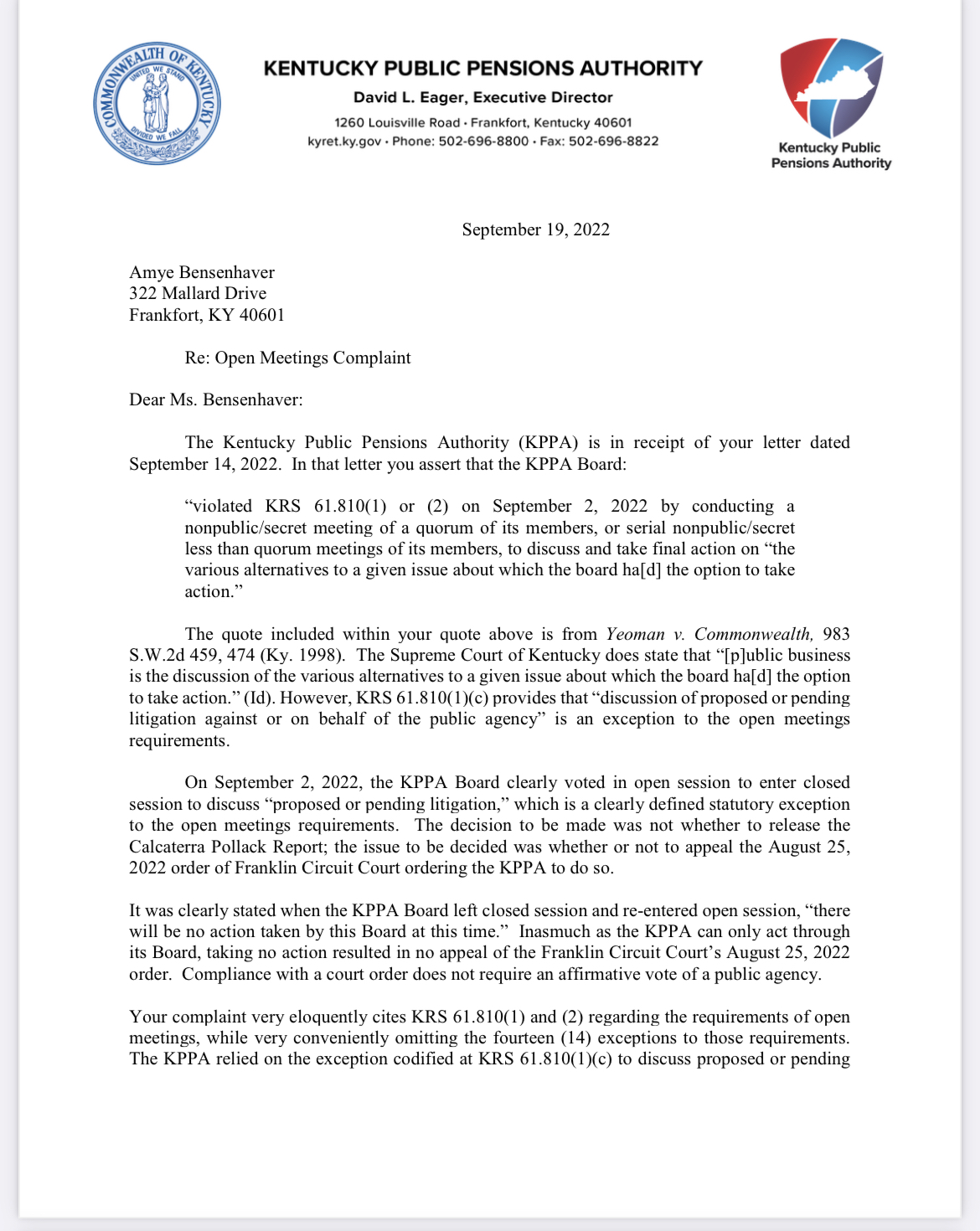

On September 14, we submitted an open meetings complaint to the KPPA Board of Trustees alleging that — in the period between its decision to take no action at the conclusion of its September 2 special meeting and notification to open records requesters Glenn Cohen and Jordan White later that day that the Calcaterra Report would be released on September 6 — the KPPA’s board of trustees violated the fundamental mandate of the open meetings law requiring that “[a]ll meetings of a quorum of the members of any public agency at which any public business is discussed or at which any action is taken by the agency, shall be public meetings, open to the public at all times.”

We did not allege that the closed meeting to discuss “litigation” was improper. Instead, we focused on the board’s failure to take a final public action/vote on the two alternative courses of action (to appeal OR not to appeal the Franklin Circuit Court’s orders) available to it.

Since KPPA could only act through its Board of Trustees, this omission was indicative of illegal backroom decision making that precluded the public from ascertaining how each trustee voted and whether the vote was unanimous or divided.

After all, the County Employees Retirement System publicly voted to recommend foregoing appeals and comply with the court’s orders the day before. And on May 26, 2021, KPPA’s Board voted not to "intervene in the attorney general's amended complaint in the Mayberry action or to take any actions against any party in the Mayberry action at this time.”

Both examples of public trustee decisions “not to act.”

Two timely KPPA responses arrived on September 19.

KPPA’s response to our open records request recited the same boilerplate attorney client/work product word salad that drew Judge Shepherd’s ire in his recent opinions directing KPPA to release the investigative findings in the $1.2 million Calcaterra Pollack report — and prompted him to ask “whether the purpose and intent of the CP Report was to fully investigate and explain all the relevant facts (and to determine if the KPPA and its employees made mistakes), or if the CP Report was commissioned to cover up or minimize KPPA’s mistakes.”

KPPA’s response to our open meetings complaint was predicated on the theory that action on whether to comply with the court’s orders required no public vote while the decision not to comply with the court’s order required a public vote. “Taking no action resulted in no appeal of the Franklin Circuit Court's August 25, 2022, order. Compliance with a court order does not require an affirmative vote of a public agency.”

A clever but ultimately indefensible legal ruse which ignores that “the express purpose of the Open Meetings Act: to maximize notice of public meetings and actions.

“The failure to comply with the strict letter of the law in conducting meetings of a public agency violates the public good.”

https://caselaw.findlaw.com/ky-supreme-court/1012466.html

The “public good” inspired the architects of Kentucky’s open government laws to codify the right to know through meetings and records access in 1974 and 1976 respectively.

In 2019, Auditor Mike Harmon declared that the retirements systems had “abdicated their responsibilities under the Open Records Act," as well as specific duties assigned to them by law in 2017's SB 2 "to improve transparency regarding the administration of the [retirement] systems.”

https://www.kyopengov.org/node/1332

In 2020, the retirement systems commissioned an investigative report into “specific investment activities conducted by the Kentucky Retirement Systems to determine if there are any improper or illegal activities on the part of the parties involved” at a cost of $1.2 million to the public, assuring the public — as well as the courts — that it would make the report accessible to the public.

In 2021, the newly established Kentucky Public Pension Authority denied multiple open records requests for that now infamous report — a report that was largely devoid of information not already publicly available, suggesting to the Franklin Circuit Court a “cover up” obtained through a questionable bid solicitation.

In 2022, KPPA balks at the notion that it owes the public — who paid for the report — anything more than minimal (and long overdue) compliance with court ordered disclosure. Trotting out the same tired and ultimately unsuccessful arguments, it stubbornly ignores the fact that the public also paid for recommendations on investment best practices and that the public is entitled to monitor the progress made in implementing those recommendations, i.e., whether we got what we paid for.

KPPA demonstrates equal contempt for the public’s ability to hold its board of trustees accountable through the open meetings law for its final decision to release the report — how each trustee voted and if the vote was unanimous or divided — arguing that the decision to comply with the court’s orders requires no decision at all.

Abuses will continue to occur “as long as they remain effectively shielded from public scrutiny." In the face of demands for changes in attitude, if not in administration, KPPA continues to ignore the public’s right to know and, ultimately, the public good.