At the conclusion of a sometimes contentious debate, the House Judiciary Committee advanced SB 63 to the House Floor by a vote of 10 ayes, one no, and three passes.

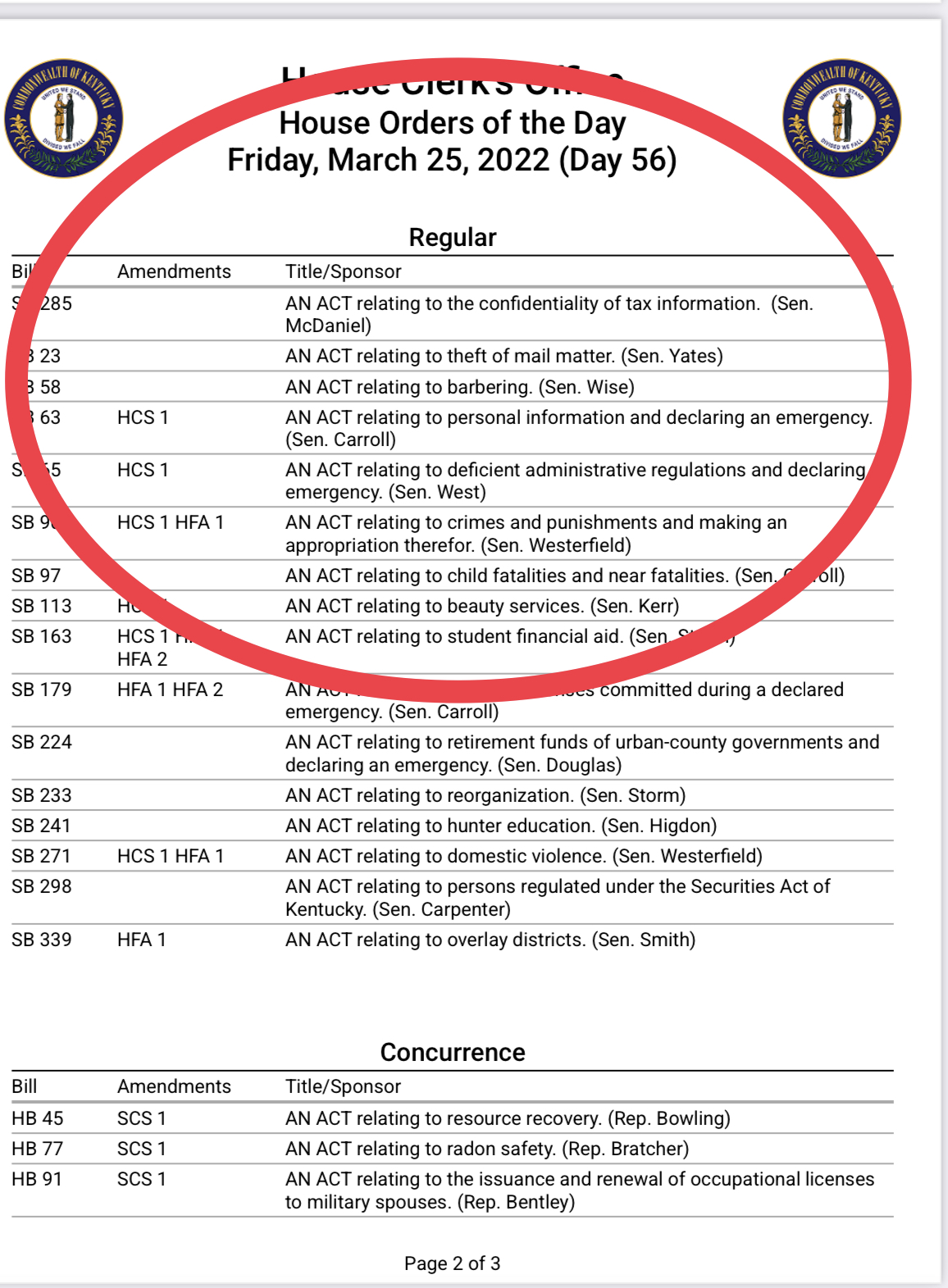

It is posted in the Orders of the Day for March 25, and is likely to pass by a substantial vote. If so, it will return to the Senate — where it originated —to consider House revisions. It will go to the Governor for signature if the Senate adopts those revisions. In 2021, the Governor vetoed a similar bill.

SB 63 is sponsored by Senator Danny Carroll and championed by Representative John Blanton. It’s stated aim is to provide enhanced protection to certain judicial and law enforcement officers by preventing disclosure of their ‘personally identifiable information’ in public records — a laudable goal by any reckoning but one that will not be advanced by the bill’s convoluted language and conflicting provisions.

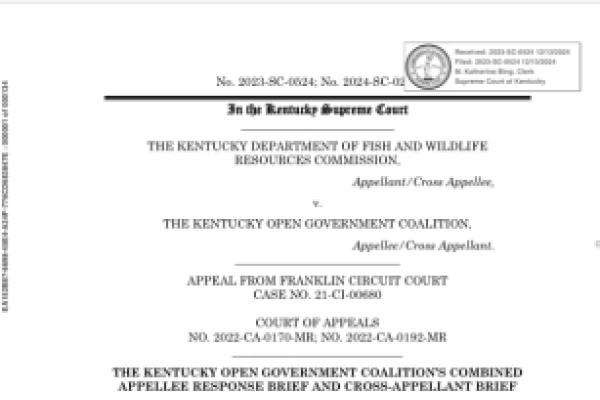

An early critic of SB 63, and past iterations of the bill, the Kentucky Open Government Coalition submitted a Statement of Opposition to the full membership of both chambers as well as the members of the committees to which SB 63 was assigned.

A copy of our full statement can be found at:

https://kyopengov.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/2022-01-24%20Statemen…

In the brief committee discussion of SB 63 on March 23, Carroll once again cited a 400% increase in threats against federal judges and an unprecedented increase in line of duty deaths of police officers — declaring that the need for the bill was never greater — but focused on recent revisions to the SB 63 rather than implementation.

Kentucky Press Association counsel Michael Abate expressed his client’s “strong opposition” to SB 63, characterizing the bill as a “non-administratable” and unreasonable restriction on free speech and a free press. He cited several example of systemic reform resulting from the use of public records in reporting that would not have been possible under SB 63. This includes, he noted, reporting that exposed the Cabinet for Health and Family Services’ failure to provide adequate protection to children under its supervision; the use of no-knock warrants in the Breonna Taylor reporting; and the bribery scandal associated with former Deputy Attorney General Tim Longmeyer that landed him in prison.

Abate also described the nearly insurmountable challenges associated with implementation of the model law — on which SB 63 is based — in New Jersey.

Carroll dismissed Abate’s concerns, noting that SB 63 does not erect an impenetrable barrier to personally identifiable information since the open records law authorizes a court to order disclosure.

(That is, of course, if the requester has the time and resources to battle these cases out in court, the agency is keen to defend each such case in court, and the courts have the resources to absorb a significant increase in their caseload.)

Rep. Blanton’s barely concealed contempt for Abate’s “long, twisted, attorney’s response” to his question about disclosure of work location suggests the tenor of the discussion.

This, along with Rep. Kim Moser’s suggestion that SB 63 does not go far enough, and Carroll’s epiphany that “the media will never support this bill,” is indicative of lawmakers’ abysmal lack of understanding of the open records law and SB 63’s likely impact on that law.

Watch it here for yourself at:

https://ket.org/share/legislature/archives/?nola=WGAOS+023263&stream=aH…

And as you are watching, please keep in mind that the Kentucky Open Government Coalition — representing the public’s interest to the best of our abilities — has never, and as it currently stands, will never, support SB 63.

A request for veto of SB 63 that will be submitted to the Governor upon its nearly inevitable final passage, the full text of which is set forth below, reflects our strong opposition to the bill, and our belief that:

“If it becomes law, SB 63 will irrevocably reverse fifty years of progress Kentucky has made in holding public officials and agencies accountable through records access. The public will censor itself in making requests and sharing information of vital public interest and public agencies will censor themselves in discharging their statutory duties. Threatened with civil liability for prohibited disclosures, the free flow of public information in Kentucky will become a trickle.”

We entreat the Governor “to veto Senate Bill 63, ‘An Act relating to personal information and declaring an emergency.’

“It is our position that SB 63 will adversely affect both the public, and the public officials it is intended to protect, by creating additional burdens on each and eliminating few, if any, of the ills it targets. It will disrupt Kentucky’s nearly fifty year old public records law by reversing the statutory presumption favoring access to public records in favor of a statutory scheme aimed at impeding the public’s right to know.

“Specifically, we oppose SB 63 for the following reasons:

“• SB 63 fails to address public agency implementation, leaving public agencies with the impossible task of erasing personally identifiable information from public records while using those records to perform their ‘routine functions.’ Challenges associated with implementation of New Jersey’s ‘Daniel’s Law,’ the state law on which SB 63 is based, necessitated suspension of that law, and immediate statutory revision, at considerable cost to the state and no demonstrable gain to public safety.

“• With few, if any, exceptions, the personally identifiable information to which SB 63 extends protection, is already shielded from disclosure by KRS 61.878(1)(a), the Open Records Act privacy exception, subject to a ‘weighing of competing public and private interest’ analysis that render these ‘enhanced’ protections largely redundant.This ensures that public officers cannot erect barriers to public information that directly advances the public’s right to know simply because that information is ‘inconvenient’ or ‘embarrassing’ to them if disclosed (e.g., the ‘home address’ of an elected official who does not qualify for office by virtue of his residency status or the ‘physical address’ of a public employee who has abandoned his designated workstation).

“• Public officials across the state -- property valuation administrators, county clerks, and city clerks -- have expressed grave concern about implementation of SB 63 in at least two recently published analyses of the bill. Kentucky’s Legislative Research Commission staff raised similar concerns in a February 22 ‘local mandate statement,’ alerting lawmakers:

“‘It is unknown how many public officers, or their immediate family members, will request the exemption from disclosure of [personally identifiable information] the impact is indeterminable. With regards to cities, the Kentucky League of Cities estimates that nearly 11,000 city employees within police, fire/EMS, and corrections departments plus around 17,000 volunteer firefighters would qualify as a public officer. KLC also referenced the 8,814 retired members, as of June 2021, in CERS Hazardous and the approximately 1,300 combined retirees and beneficiaries in Lexington’s Policemen’s and Firefighters’ Retirement Fund and City Employees’ Pension Fund. Some cities have their public safety staff in CERS Nonhazardous; therefore, a portion of retirees in that plan may also qualify as a public officer.’

“‘The legislation may prevent localities from publishing certain delinquent taxpayers and/or selling all delinquent tax bills to a third party. With respect to county clerks, the legislation is anticipated to increase duties in already understaffed offices. With the various documents under their purview including those relating to marriages, voter data, vehicle information; there are concerns about the ability to comply. For city clerks, the duties would increase more in smaller municipalities without staff specifically designated to handle only open records requests. In some municipalities, police departments, fire, and emergency management service departments handle their own open records requests and in others, those duties are assigned to city clerk personnel.’ The argument that public agencies’ will continue to perform ‘routine functions’ uninterrupted because lawmakers have legislatively directed that they do so is best evidence that lawmakers are divorced from reality.

https://www.wdrb.com/in-depth/protection-or-logistical-nightmare-kentuc…

https://www.messenger-inquirer.com/news/bill-would-exempt-public-offici…

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/recorddocuments/note/22RS/sb63/LM.pdf

“If it becomes law, SB 63 will irrevocably reverse fifty years of progress Kentucky has made in holding public officials and agencies accountable through records access. The public will censor itself in making requests and sharing information of vital public interest andpublic agencies will censor themselves in discharging their statutory duties. Threatened with civil liability for prohibited disclosures, the free flow of public information in Kentucky will become a trickle.

“The primary impetus for SB 63 is the legislative finding that “personal information is easily published over the Internet and social media and there has been an increase in death threats and death of judges and other public officials.” Proponents and opponents of SB 63 agree that protection of public officers is a worthy goal. They disagree about whether SB 63 is a realistic means to that end.

“We urge you veto SB 63 to avoid upending the nearly fifty year old Open Records Act in the faint hope of eradicating a far more pervasive societal malaise.”