The death of former Governor Brereton Jones serves as a reminder that short term solutions to open records disputes can have long term -- and often unwelcome -- consequences. His open records legacy is not an entirely happy one.

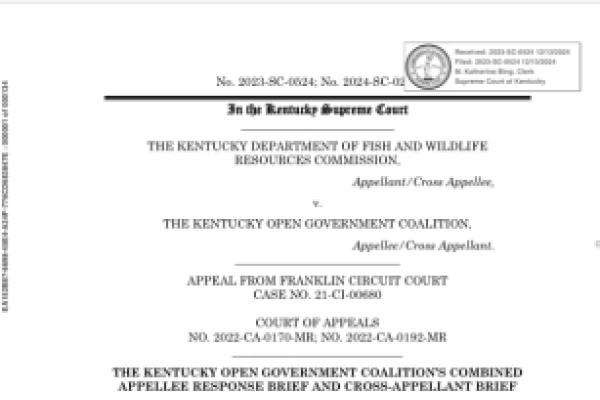

In 1992, Courier Journal reporter Tom Loftus submitted a request to inspect Governor Jones's daily schedules for the period from December 11, 1991, through the date of the request.

Jones denied Loftus's request. His office relied on the personal privacy exception, KRS 61.878(1)(a), asserting that the schedule was "a mixture of family, social and public events, it being impossible to schedule his public events without keeping track of his private schedule."

The Governor also asserted that the schedule was a preliminary document within the meaning of KRS 61.878(1)(i), then found at KRS 61.878(1)(h), "in that unforeseeable circumstances often require last minute cancellation of events that appear on the schedule." In support, Jones cited OAG 78-626, an early open records opinion affirming the City of Louisville's denial of the mayor's calendar on the basis of the personal privacy and preliminary documents exceptions.

https://www.ag.ky.gov/Resources/orom/1993/93ORD025.htm

Following considerable internal office debate, the Attorney General affirmed the denial, relying on the 1991 California case, Times Mirror Company v. Superior Court of Sacramento, that became the lynchpin of the Kentucky appellate court's opinion -- also affirming the Governor's denial.

https://law.justia.com/cases/california/supreme-court/3d/53/1325.html

In essence, the California Supreme Court held that "the Governor's Office properly withheld the Governor's appointment calendar under the 'public interest' exemption, reasoning that although the calendar was not covered by California's corresponding 'preliminary documents' exception, its disclosure would jeopardize the decisionmaking, or 'deliberative process,' which that exemption was intended to protect, by inhibiting access 'to the broad spectrum of persons and viewpoints which he requires to govern effectively.'"

https://www.ag.ky.gov/Resources/orom/1993/93ORD025.htm (citing Times Mirror)

The open records decision was one of many that Attorney General's merit staff hotly debated with non-merit staff but one that could not be deemed "legally unprincipled" -- given the existence of an earlier Kentucky attorney general's opinion affirming Louisville's denial of access to the mayor's calendar and an appellate court opinion, albeit one "emanat[ing] from a sister state's court of last resort."

I signed it, albeit reluctantly.

The Courier appealed the open records decision to the Kentucky Court of Appeals where it was affirmed. I'm always struck by the tone the court set for the case early in its analysis:

"As is customary in the open records act appeals, we are never informed just what the media seeks and for what purpose. This leads to the conclusion that all these efforts are a fishing expedition upon which to base some speculative publication. Be that as it may, we now turn to the legal issue."

https://www.casemine.com/judgement/us/59148455add7b049344b5544/amp

Since the purpose of an open records request was never relevant to the resolution of an open records dispute in 1992 -- and has since become relevant only to the extent the requester's purpose is a commercial (versus a non-commercial) one -- this quotation casts an unfortunate shadow on the case.

Even more unfortunate is the manner in which Courier Journal v Jones has since been expanded beyond its intended limits.

In 22-ORD-026, for example, the Attorney General relied on Courier Journal v Jones to affirm his own denial of a request for "emails that discuss the scheduling of events, or certain videos taken during the [Ark Park] event, as preliminary under KRS 61.878(1)(i)."

https://www.ag.ky.gov/Resources/orom/2022/22-ORD-026.pdf

Based on the Jones case, worse was, and is, to come.

The Courier elected to forego further appeal by petition for discretionary review to the Kentucky Supreme Court in 1995 as a new Governor, Paul Patton, prepared to take office with a commitment to make his schedule available to the public and the media. Succeeding governors did not so blithely release their schedules. Its unlikely a "Governor Cameron" would happily produce his schedule.

https://www.ag.ky.gov/Resources/orom/2022/22-ORD-026.pdf

https://dev.kyopengov.org/node/1482

Perhaps it is "too soon" to remember a less auspicious moment in Governor Jones's administration. He is gone and his achievements are celebrated.

But the unfortunate legal precedent to which his name is attached -- and the even more unfortunate abuse of that precedent -- remains.